Hen & Rabbits, Feet & Animals; Some Thoughts on Representing Word Problems Graphically

Judah L. Schwartz

Word problems that are solved by formulating a pair of simultaneous linear equations might well appear in an algebra classroom anywhere in the world. We offer some examples and analyze two different graphical representations of one of the problems. One of these representations is familiar and commonplace. The other is unusual and invites one to consider new analytic settings for some old familiar tools. Both of these representations draw heavily on earlier work by the author on the Semantic Aspects of Quantity The problems: Word problems in algebra are often classified by their superficial content – there are rate problems, mixture problems, coin problems, etc. Here are five structurally identical but contextually different word problems that are typical of the problems that are presented by teachers to their algebra students in classrooms around the world. For the most part, such problems serve a vehicle for students to learn some tools of algebraic manipulation. Once the system of linear equations that describes each of these problems is formulated, almost no subsequent attention is devoted to the semantics of the situation being modeled. I. Tickets for a minor league baseball game cost $10 for an adult and $4 for a child. A total of 400 tickets were sold and $3,400 was collected. How many adult tickets were sold and how many children’s tickets were sold? Answer [400 adult tickets, 100 child tickets] II. A coffee shop wishes to prepare 24 lbs of coffee by blending cheap coffee that sells for $ 5/lb and more expensive coffee that sells for $ 10/lb. If they want to sell the blended coffee for a total of $200, how many pounds of each type of coffee should they use? Answer [ 16 lbs of expensive coffee, 8 lb of cheap coffee] III. A farmer has 50 animals. Some are hens and some are rabbits. Among them they have a total of 140 legs. How many hens and how many rabbits does the farmer have? Answer [30 hens, 20 rabbits] IV. Jane has 8 coins. Some are dimes and some are quarters. Among

them they have a total value of $1.55 How many dimes and how many quarters does

Jane have? Answer [5 quarters, 3 dimes]. V. When flying with the wind, an airplane moves at 600 mi/hr with respect to the ground. On the other hand, when flying against the wind moves at 40 mi/hr with respect to the ground. How fast does the airplane move with respect to the ground when there is no wind? How fast does the wind blow? The Equations In order to formulate the equations necessary to solve these problems one must designate variables.[1] I. [number of Adult tickets – A number of Children’s tickets – C] A + C = 400 tickets 10 A + 4 C = 3400 $

II. [Weight of cheap coffee – C weight of expensive coffee - E] C + E = 24 lb 5C + 10 E = 200 $

III. [number of hens – H number of rabbits – R] H + R = 50 animals 2H + 4R = 140 feet

IV. [number of dimes – D number of quarters – Q]

D + Q = 8 coins 10 D + 25 Q = 155 cents

V. [ velocity of plane with respect to ground – V wind seed – W] V + W = 600 mi/hr V – W = 400 mi/hr These equations look like those solved (or not solved) in most classrooms around the world. Unfortunately, in these equations half the coefficients of the variables are missing and the other half are left with their units undefined. Consider for example Problem III – because animals are a superset of both hens and rabbits we allow ourselves to write such an equation. It would seem that we are writing H hens + R rabbits = 50 animals Is this is yet another case of relaxing the prohibition on “adding apples and oranges”? Can one really add hens and rabbits? The equation H + R = 50 animals in Problem III should be written 1H + 1R = 50 animals and the newly appearing coefficients have units. The 1 preceding the H has the dimension of 1 animal/hen and the 1 preceding the R has the dimension 1 animal/rabbit. Written in its entirety the first equation in Problem III becomes 1 animal/hen · H hens + 1 animal/rabbit · R rabbits = 50 animals which is now dimensionally correct – both the left and right sides of the equation refer to animals. What do the units “animal/hen” and “animal/rabbit” mean, and why are they not normally written? Since a hen is an animal the only possible numerical value that can be attached to the unit “animal/hen” is one. Similarly for the unit “animal/rabbit”. This fact enables us to neglect writing the 1 and the associated unit and as a result we encounter the seeming “adding apples and oranges” inconsistency.

A similar sort of dimensional issue is true with the second of the two equations in each of our illustrative examples. The second equation in Problem III written in dimensionally correct form is 2 feet/hen · H hens + 4 feet/rabbit · R rabbits = 140 feet Solving the equations

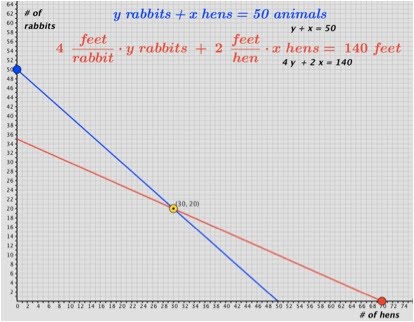

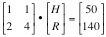

In the {hens, rabbits} plane Normally these equations are solved symbolically using one of several techniques of solution. Alternatively, the problem may be solved graphically by plotting both equations in the plane of the variables – Here for example is the graphical representation of the Hen/Rabbit problem plotted in the {hen, rabbit} plane.

Every point in the {hen, rabbit} plane with non-negative integer coordinates represents some number of hens and some number of rabbits. Every point with integer coordinates on the blue line represents some mixture of hens and rabbits totaling 50 animals. Every point with integer coordinates on the red line represents some mixture of hens and rabbits that have a total of 140 feet. The point where the lines intersect is the point that represents that mixture of 50 animals that has 140 feet. It is important to point out that unless one first solves this problem symbolically, the “graphical target”, i.e. the point of intersection of the two plotted functions is not known in advance of the plotting of the functions. This illustration is drawn from the applet Hens & Rabbits I in the “Modeling

& Formulating” section of this website. By varying the points of intersection of the two functions with the coordinate axes one can explore an ensemble of equivalent problems.

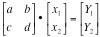

Matrix solution of the equations – Cramer’s Rule A pair of simultaneous linear equations is of the form or Y = Ax in matrix notation when the elements of the square matrix, a, b, c and d are known as well as the values of Y1 and Y2. The problem becomes one of finding the elements of the unknown column vector whose elements are x1 and x2.

The solution of this set of equations, written in matrix form is x = A-1Y where A-1 is the matrix inverse of A.

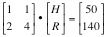

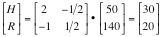

If we formulate our problem as a linear matrix problem – where the unknowns are the elements of the column vector H and R .

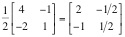

The inverse of this matrix is Multiplying our matrix equation on the left by the inverse of the coefficient matrix[2] , we obtain The reader is urged to pay particular attention to the units of each of the matrix elements. The two elements of the “unknown” column matrix, H and R, have different units. Clearly, this column matrix represents a vector in the {hen, rabbit} plane. On the other hand, the elements of the “data” column matrix, 50 animals and 140 feet, are entirely different.[3] The equation can be thought of as a transformation of a vector in the {hen, rabbit} plane into a given and known vector in the {animal, feet} plane.

It is important to note that when using Cramer’s Rule it is possible solve for one of the variables without solving for the other. On the other hand, the traditional graphical solution, of necessity, yields the solution for both H and R simultaneously.

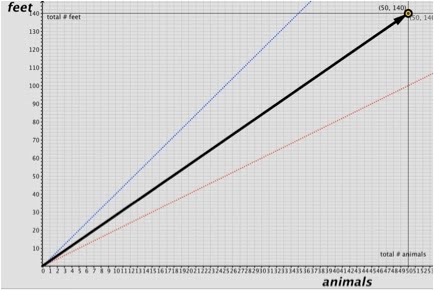

Solving the Equations In the {animals, feet} plane In a sense this last result is curious – every point in the {hen, rabbit} plane corresponds to a point in the {animals. feet} plane although the converse is NOT true – there are points in the {animals, feet} plane corresponding to fish, spiders and centipedes. The consequences of this fact are interesting. It permits us to consider solving our problem in the {animals, feet} plane directly. Suppose, however, that we represent the problem not in the {hens, rabbits} plane, but rather in the {animals, feet} plane. In this plane one can immediately mark the “graphical target” of {50, animals, 140 feet}. The “graphical target” is available at the outset. One can draw a vector from the origin {0 animals, 0 feet} to this target point. As we shall soon see, this vector is the vector sum of a “rabbit” vector and a “hen” vector. Because hens have two feet, all possible values of numbers of hens lie on a line of slope 2 feet/animal (red). Similarly all possible values of numbers of rabbits lie on a line of slope 4 feet/animal (blue).

Every point in the {animal, feet} plane with integer coordinates represents some number of animals and some number of feet. Note that many points denote totally fictitious creatures with unreasonable leg counts. Every point with integer coordinates on the thin blue line [slope = 4 feet/animal] represents some number of four legged animals – in this case, rabbits. Every point with integer coordinates on the thin red line [slope = 2 feet/animal] represents some number of two legged animals – in this case, hens. Note that all of the points in the first quadrant of the {hen, rabbit} plane are mapped into the points between (and on) the thin red and blue lines. The hen axis maps onto the red line; the rabbit axis onto the blue line.

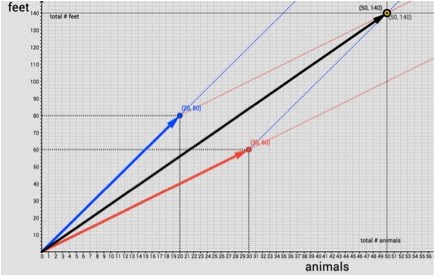

The solution to the problem which is represented by an integer lattice point in the {hens, rabbits} plane is represented differently in the {animals, feet} plane. In this plane there is a “rabbit vector” [with components animals and feet] which lies along the light blue line and a “hen vector” [with components animals and feet] which lies along the light red line. When the blue rabbit vector is of the proper length [20 animals, 80 feet] and the red hen vector is the proper length [30 animals, 60 feet], the black vector is the “sum” of the “rabbit vector” and the “hen vector” and goes from the point {0 animals, 0 feet} to the point {50 animals, 140 feet} – which, of necessity, must be an integer lattice point in the {animals, feet} plane that lies somewhere between or on the red and blue lines.

When the black vector is [50 animals, 140 feet], then... ...the thick blue vector drawn from the origin to the point {20 animals, 80 feet} has a horizontal component of 20 animals and a vertical component of 80 feet. ...the thick red vector drawn from the origin to the point {30 animals, 60 feet} has a horizontal component of 30 animals and a vertical component of 60 feet. ...the thick black vector drawn from the origin to the point {50 animals, 140 feet} is the vector sum of the red and blue vectors. It may be thought of as representing a population of 50 animals, each of which has 2.8 feet!!

Having set the “graphical target” at the outset, one can now ask what linear combination of a red vector (hens) and a blue vector (rabbits) will yield the black vector. Moving the blue and red points along their respective lines is now a simple exercise in vector addition that leads to the solution (as pictured). The reader will note that in this method of graphical solution in the {animals, feet} plane it is possible to solve for each of the variables separately.

What kinds of vectors are these? Can they

indeed be called vectors? What vector properties do they have?

This illustration is drawn from the applet Hens & Rabbits II in the “Modeling & Formulating” section of this website. By dragging the large red and blue dots along the red and blue lines respectively, one can explore an ensemble of equivalent problems. Note that the addition of horizontal components of red & blue vectors corresponds to the first of the two equations we wrote for this problem 1 animal/hen · H hens + 1 animal/rabbit · R rabbits = 50 animals and the addition of vertical components of red and blue vectors corresponds to the second of the two equations we wrote for this problem 2 feet/hen · H hens + 4 feet/rabbit · R rabbits = 140 feet In contrast to the standard graphical representation of this problem, however we never had to formulate the two linear equations or to plot them.

Implications The reader is invited to apply the analysis in this short paper to the other problems presented at the beginning of this paper, and indeed to any similar such problem that appears in the algebra curriculum. In particular, consider what the non-traditional representation of the problem would look like if both equations had coefficients whose value was not one. In my view, at the very least this alternative non-traditional method of graphically solving simultaneous linear equations broadens the set of tools available to the algebra teacher. It does more, however. It demonstrates clearly how nontraditional ways of looking at traditional material can lead to the unexpected appearance of mathematical objects and/or actions not ordinarily associated with the situation being analyzed. In this case, questions arise about how far we can carry the concept of vector. Can we define a metric in an {animal, feet} plane? Would things be different if the elements of the two basis vector were continuous rather than discrete quantities [e.g. a {distance, time} plane] ? Would things be different if the elements of the two basis vectors were similar quantities [e.g. a {weight, weight} plane] ? What kinds of products can such vectors have? What kinds of transformations can be carried out on them? Finally, because these questions all arise from an exploration of an old and familiar topic that is not often looked at by teachers with a fresh eye, for me the lesson learned is the importance of continually thinking about the power of new bottles for wonderful old wines.[1] Rather than denote the variables by x and y, a practice that, in general, has no mnemonic value, we denote variables using letters that evoke the unknown quantities they represent. [2] Note that in constructing the inverse matrix we have used the fact that the determinant of the coefficient matrix is D = 1 animal/hen · 4 feet/rabbit – 1 animal/rabbit · 2 feet/hen = 2 animal·feet/rabbit·hen [3] The reader is invited to determine the units of each of the elements in the coefficient matrix.

mathMINDhabits by Judah L. Schwartz is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |