Computing with Adjectival Quantities - Referent-Transforming

Operations.

a. intensive and extensive quantityBefore we examine referent-transforming operations with adjectival quantity, we need to make a kind of digression. The most common referent-transforming operations are multiplication and division. By far the majority of the situations in which we are called upon to do either multiplication or division will involve a different sort of “quantity” that is neither directly counted nor measured, i.e. intensive quantity. To understand what kind of quantity this is and why it appears in almost all multiplication and division problems, let us consider the following situation with, say, coffee beans (assumed for our purpose to be a continuous quantity). Suppose we have a pile of coffee beans characterized by the three adjectival quantities; {(5.0, lb), weight of coffee} {(40.00, $), cost of coffee}{(8.00, $/lb), price/lb of coffee} If we have two such piles of coffee beans and coalesce them, it is clear that the appropriate mode of composing the quantities describing the weight and the cost of the coffee differs from the appropriate mode of composing the quantity that describes the price/lb. The weight of the coalesced pile of coffee beans is {(10.0, lb), weight of coffee} and the cost of the coalesced pile of coffee beans is {(80.00, $), cost of coffee} while the unit price of the coalesced pile of coffee beans is {(8.00, $/lb), price/lb of coffee}. The fact that the mode of composition of the price/lb adjectival quantity is different from the others is a clue. The price/lb quantity is a different sort of descriptor of the coffee. Whereas the first two quantities describe the entire pile of coffee beans, the price/lb quantity describes not only the entire pile of coffee beans but it can equally well describe a single coffee bean or a freight car full of them. It is a quantitative descriptor of a quality of the coffee and does not describe any aspect of the coffee that depends on the amount of coffee. It is called an intensive quantity. For the most part mathematical intensive quantities can be recognized by the fact that their unit measures almost always contain the word per.[1] In general, one can think of an intensive quantity as a generalization of the notion of density. Think of a solid block of pure copper. Copper at room temperature has a density of 8.92 grams per cm3 . If the block has a volume of 1000 cm3 it will have a mass of 8920 grams. A smaller block, with a volume of 10 cm3 will have a mass of about 89.2 grams. A still smaller block with a volume of .01 cm3 will have a mass of 0.0892 grams. In each case the ratio of the mass of the copper block to its volume give the same intensive quantity, i.e., 8.92 grams per cm3 . This notion of density is a mass density in that it is a measure of the mass per unit volume. In the case of the copper block we considered a pure material whose mass is uniform throughout its volume. The more general notion of density does not necessarily refer to mass nor does it really depend on uniformity. For example, suppose that following a collision, all of the bags of different varieties of instant coffees in a freight car broke open and mixed to some degree. There would be a huge pile of unevenly mixed coffee powder on the floor of the freight car. The price per pound of the coffee in the pile is a cost-density that would vary from place to place in the freight car. If you chose a cupful of coffee from one part of the freight car it would have a value that would not likely be the same as the value of a cupful of coffee chosen from a different part of the freight car. Despite the fact that the pile as a whole has a price per pound that varies from place to place in the freight car, the total price of the coffee in the freight car can be calculated. Another common example of an attribute density that varies from place to place is the population-density of a country. This density is the ratio of a number of people to an area rather than a volume. Taken as a whole, Canada has a population density of 7 persons per square mile. Clearly this does not mean that in every square mile of Canadian territory one will find 7 people. The province of Ontario has a population density of about 22 persons per square mile and the city of Toronto has a population density of about 20,000 persons per square mile. However, the population density of Toronto cannot be said to imply that in every .001 square miles one will find 20 people living. The speed of a vehicle during the course of a trip can be thought of as a kind of generalized density. In this case we consider the ratio of a distance to a time. If I drive a total of 120 miles in 3 hours my average speed for the entire trip is 40 miles per hour. Suppose that at the beginning of the trip I spent one minute accelerating from rest to a speed of 60 miles per hour. During that minute my average speed was 30 miles per hour. During a later part of the trip I might have spent 20 minutes driving a distance of 25 miles. During that period my average speed was 75 miles per hour or 1.25 miles per minute. If during that twenty minute period I drove at a constant speed then I would have driven 5 miles in 4 minutes, .25 miles in .2 minutes, .125 miles (660 feet) in .1 minutes (6 seconds), 110 feet (about 7 car lengths!) in 1 second. The ratio of the distance traveled to the time it took to travel that distance remaining constant is entirely analogous to our considering smaller and smaller blocks of copper in which the ratio of the mass of the copper to the volume of that mass remained the same.[2] It should be pointed out that the assertion of an intensive quantity such as {(34.5, mi/hr), speed}, {(13.6, gm/cc), density of mercury} or {(5, candies/bag), party favor} gives no information whatsoever about the number or amount of the relevant extensive quantities, in these cases miles, hours, grams, cubic-centimeters, candies or bags. The

statement of an intensive quantity is a statement of a relationship between

quantities. In general, the

related quantities are extensive quantities, but this need not be the

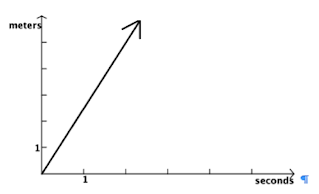

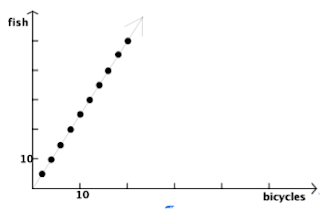

case. Consider, for example, acceleration which has the units [(distance / time) / time]. If the referent is homogeneous, then the relationship holds for all parts of the referent entity. If not, then the intensive quantity is a local property of the referent entity. In our example of the instant coffee in the freight car, the mass/volume density varied from place to place in the freight car. In our example of the car trip the distance/time density was different at different times. Although it may seem odd to refer to a relationship as a quantity, an important reason for doing so is that these relationships can be quantified and ordering and arithmetic operations can be carried out with these quantities. The fact that the core of the idea of an intensive quantity is a relationship makes the representing of it difficult. Let us consider how we might represent different sorts of quantities graphically. An extensive quantity such as {(5, meters), distance} can be represented as a suitably placed point on a suitable (in this case, distance) number line [more properly, quantity line], as can the extensive quantity {(2, seconds), time}. The intensive quantity {(5/2, meters/seconds), speed} cannot be represented on either of these quantity lines[3] but rather must be represented as an infinite number of points that lie on a straight line in the meters-seconds plane. (Figure 1.)  In the case of discrete adjectival quantities, such as {5, fish} and {2, bicycles} and the related intensive quantity {5/2, fish/bicycle} we have a similar situation. We might indicate {5, fish} as a suitable point on a “fish quantity line” and {2, bicycles} as a suitable point on a “bicycle quantity line”. The intensive quantity {5/2, fish/bicycle} cannot be represented on either of these quantity lines but rather must be represented as an infinite number of points that lie on a straight line in the fish-bicycle plane. Because of the discrete nature of both fish and bicycles, all of the points must have integer coordinates in the fish-bicycle plane.  It is probably desirable to devise some sort of pictorial representation of this kind of quantity in addition to the formal graphical representation.[3] We know how to display pictorial representations of {5, fish} and {2, bicycles} by drawing pictures of five fish and two bicycles. But how can we make a pictorial representation of {5/2, fish/bicycle} that has the property that no specific number of fish or specific number of bicycles is being referred to but only the relationship between these two quantities? One possibility is to call upon the entire fish-bicycle plane (Kaput etal, 1986). Suppose we tessellate the plane with icons of small fish and bicycles or initials of the words fish and bicycle and define a suitable set of sample sizes with which to sample the icons in the plane. If the tessellation is made properly, then it will turn out that a rectangular sample of size 1 x 7 or 7 x 1 will enclose 5 fish and 2 bicycles no matter where in the plane it is placed. FFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbb FFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbF FFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFF FFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFF FbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFF bbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFF FFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbbFFFFFbb Similarly, no matter where it is placed in the plane a rectangular sample of 2 x 7 or 7 x 2 will enclose 10 fish and 4 bicycles, and a rectangular array of 10 x 14 will enclose 100 fish and 40 bicycles, etc. Since an intensive quantity is formed (in general) from two extensive quantities, each of which might be either discrete (D) or continuous (C), we have the following possibilities; Intensive quantities of the form D/D are relationships between two sets of discrete extensive quantities, e.g. children/family or candies/bag Intensive quantities of the form C/D and D/C are relationships between a set of discrete and a set of continuous extensive quantities, e.g. gallons/bucket or persons/year Intensive quantities of the form C/C are relationships between two sets of continuous extensive quantities, e.g. miles/hour or grams/cubic centimeter One final remark about intensive quantity. Suppose we think about a penny that is dropped down a well. The speed of the penny when you first release it from your hand is {(0, meters/second), speed}. The penny falls faster and faster until it hits the bottom. At different times after its release from your hand the penny has different speeds. Acceleration is a measure of how fast the speed of the penny is changing. In our terms we might think of it as a speed-time density. This seems to mean that speed is an extensive quantity even though we treated it earlier as an intensive quantity. Speed is indeed an intensive quantity if we are interested in its relation to the quantities from which it is composed. If we are not, then there is no reason not to treat it as an extensive quantity. It may seem that the notion of intensive quantity, so suggestive of the concept of derivative in the calculus, is an esoteric one and cannot seriously be expected to play an important role in the mathematics of the early grades. It will turn out, however, that intensive quantity is essential to the understanding of the vast majority of situations that call for the arithmetic acts of multiplication and division.

b. what's wrong with repeated addition and subtraction We now turn to the major business of this section, i.e., referent-transforming operations with adjectival quantity. By far the most common such operations are multiplication and division. Normally, multiplication is introduced to youngsters as an efficient way of doing repeated addition, and division as an efficient way of solving the problem of equitably sharing some set of desirable objects among children. There are serious flaws with each of these approaches. Some of these flaws are procedural in nature and give rise to students having mechanical difficulties and others are conceptual in nature and stand in the way of a proper understanding of multiplication and division. We turn first to the procedural flaws. Suppose

we seek to count the number of dots in an array that contains 3 rows of dots

with each row containing 4 dots. Clearly the array looks like: * * * * A multiplicative procedure that does not yield {12, dots} is {4, dots} x {3, dots} = {12, dots2} and not {12, dots} It is possible to construct a product of nominal and adjectival quantities such as 3 x {4, dots} or 4 x {3, dots} but this suffers from two difficulties. The first is that we have not defined operations between nominal and adjectival quantities, and second, how are we supposed to know to what the nominal quantity refers? So far we have not properly mathematized the quantities referred to in the original verbal statement of the problem. They are in fact {3, rows} and {4, dots/row}. Note that the {3, rows} x {4, dots/row} = {12, dots} does lead to the correct number of dots. Note that this multiplication involves the product of one factor that is intensive in nature and one that is extensive. We will return to this observation in the next section.

The reader will note that the equivalent formulation of a product {3, dots/column} x {4, columns) = {12, dots} yields two factors with entirely different referents from those in the first product. Thus we see that the factoring of the magnitude of an adjectival quantity does not in any way constrain the “factoring” of its referent. Here, for example, is the same array “factored” in yet a different way * * * * * * * * * * * * namely {3, dots/L-block} x {4, L-blocks} = {12, dots}. Let us continue our consideration of multiplication as repeated addition. Here are two different multiplication problems; {5.0, candies/bag, kind of party favor} x {6, bags} and {14.5, mi/hr, average speed on trip} x {3.2, hr, time trip takes}. The repeated addition model, which works easily in the first instance, suggests that we build sequentially the following table of associated extensive quantities; {5, candies} corresponds to {1, bag} {10, candies} corresponds to {2, bags} {15, candies} corresponds to {3, bags} {20, candies} corresponds to {4, bags} {25, candies} corresponds to {5, bags} {30, candies} corresponds to {6, bags}[4] The method clearly depends on our ability to translate the relationship expressed by the intensive quantity {5.0, candies/bag, kind of party favor} into an association between two discrete extensive quantities, i.e. candies and bags which can then be iterated the requisite integer number of times, in this instance 6. It also depends quite explicitly on the presumption of homogeneity, i.e. that the intensive quantity {5.0, candies/bag, kind of party favor} characterizes each of the bags in the ensemble. If we attempt to apply this same sort of analysis to the second of the problems cited above. {14.5, mi/hr, average speed on trip} x {3.2, hr, time trip takes}. we immediately discover that the strategy of iterating the association of miles and hours an integer number of times simply can't be carried out in this instance. Finally, perhaps most lethal to the idea of multiplication as repeated addition, is the following example (and others of its ilk). {0.5, mi/hr, average speed of moving walkway} x {1/50, hr, time spent on moving walkway} = {0.01, mi. length of walkway} The magnitude of the product is smaller than the magnitudes of each of the factors. How does one reconcile this result with the concept of repeated addition – the result of addition as an action normally means a sum that is larger than all of the addends. In a similar fashion we can consider two division problems that will serve to underline the difficulties with the way division is normally presented to youngsters in schools. Suppose one has a total of {30, candies} distributed uniformly at the rate of {5, candies/bag} among {6, bags}. The quantity {30, candies} / {6, bags} can be assumed to characterize each of the bags and be a local property of the referent situation. The equivalent quantity {5, candies/bag}[5] can be computed by repeatedly subtracting 6 from 30 and recognizing that this can be done 5 times. What is happening when one does this sharing of candies among bags is an acting out of {1, candy/bag}+{1, candy/bag}+{1, candy/bag}+{1, candy/bag}+{1, candy/bag} This division by repeated subtraction is the mirror image of multiplication by repeated addition. Suppose, on the other hand, one wishes to divide the quantity {33, candies} by the quantity {6, bags} It is clear that the mental image of sharing or partitioning one quantity evenly does not work easily here. When first introduced to division students are taught that 33/6 is 5 R 3 (read as 5 remainder 3) When dealing with adjectival quantity, how do we answer the question of the referents of the symbols 5 and 3? They are clearly different from one another. Specifically, they are {5, candies/bag} and {3, candies}[6] There is yet another procedural way in which the repeated addition model of multiplication, or its mirror image, the sharing model of division, fails. These models, which, as we have seen, can sometime be used with discrete adjectival quantity, lead students to expect that multiplication always results in a new quantity which is larger in magnitude than either of the factors in the product and that division always leads to a quotient which is smaller in magnitude than the dividend. Indeed, the common parlance usage of the English words multiply and divide reinforce this expectation. In addition to these procedural flaws of “repeated addition” and “sharing” models of multiplication and division, there is, in my view, a deep conceptual flaw that inheres in these formulations. They lead the student to believe that the resulting computed quantity is of the same sort and has the same referent as one of the quantities that entered into the computation. As we have seen in the examples above, this is in general not true. Multiplication and division are referent-transforming compositions of adjectival quantity and addition and subtraction are referent-preserving. A pedagogic strategy for teaching referent-transforming compositions that depends on extending referent-preserving compositions misses the essential feature of that which is being introduced, i.e. that referent-transforming composition gives rise to a quantity of a new kind!

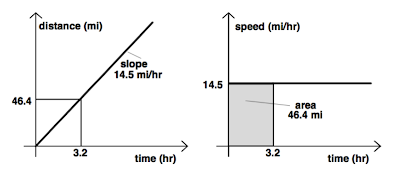

c. multiplication and division of adjectival quantitiesThe (I E E') Semantic Triad Fortunately, we are not obliged to rely on “repeated addition” and “sharing” to provide our students with mental models of multiplication and division. It is possible to approach the problem of providing students with a mental model of the multiplication and division of adjectival quantity that is not limiting in the ways we discussed above. In the interests of specificity let us consider the previous problem involving the three related quantities E' {(46.4, mi), distance traveled} E {(3.2, hr), time trip takes} I {(14.5, mi/hr), average speed on trip} These three quantities can be related to one another via multiplication operations or via division operations. However, because of the commutativity of multiplication, there is only one distinct multiplication operation relating the three quantities, i.e. I x E = E' while there are two division operations relating the three quantities, i.e. E'/ E = I and E'/ I = E The intensive quantity can be thought of explicitly as a relationship between distance and time for an infinite ensemble of trips, each of which is traversed at an average speed of 14.5 mi/hr. The correspondence between distance and time for this ensemble of trips can be illustrated in a graph such as the one we showed earlier. In the distance-time plane, a line of slope 14.5 mi/hr is drawn through the origin. Every point on the line describes a trip in the ensemble of trips described by the intensive quantity 14.5 mi/hr. The triad of quantities are linked to one another semantically and students would be well served if they were taught to think of a referent situation involving distance, time and speed. The relationship among these quantities can be expressed in three different ways.[7] There is another graphical encoding of the relationship among these quantities that can easily be constructed. In the velocity-time plane a horizontal line whose ordinate is 14.5 mi/hr is drawn. Every point on this line corresponds to a trip of a given duration. Each such point also defines an area bounded by the average velocity axis, the average velocity, the time axis and the value of the time of the trip in question. The measure of this area is the distance traveled in the course of that trip. Here then are the two graphical representations of this (I E E') triad presented side by side.  It is interesting to note that these two graphical representations of the relationship among the three quantities of interest capture the essential idea of the differential calculus that the rate of change of a function is given by its slope, and the essential idea of the integral calculus that the cumulative area under the graph of a function is a measure of cumulative effect of the changes in the function. These ideas can be introduced quite early in the curriculum to help think about and represent the semantically related triad of adjectival quantities involved in multiplication and division. When in later years, students in learning calculus are asked to think about slopes and areas under curves, they will be extending the power of some familiar ideas. There do not seem to be important differences between the behavior of discrete and continuous adjectival quantity under the referent-transforming operations of multiplication and division. All of the following cases are to be found D/D x D e.g. children / family x families D/C x C e.g. people / hour x hours C/D x D e.g. pounds / person x number of people C/C x C e.g. miles / gallon x gallons Before leaving our discussion of the (I E E') triad, it is worth addressing an issue that seems to cause a great deal of difficulty for many people, i.e. the division operation E' / E = I when both extensive quantities are discrete adjectival quantities. An example is {100, children} / {40, families} = {(2.5, children/family), average number of children per household} Note that although both children and families are count nouns and that {100, children} and {40, families} are discrete adjectival quantities the quantity {(2.5, children/family), average number of children per household} is a continuous adjectival quantity. Many people find this quantity moderately amusing, seemingly because they think it refers in some way to a portion of a child.[8] d. the conversion of unitsThe (I E E') semantic triad allows us to return to an issue that we left unresolved earlier, i.e., the conversion of units. Consider the quantity {(13.5, ft), length of bookshelf}. Another way to describe the same attribute of the same bookshelf is to use a different measure. Suppose we wish to measure the length of the bookshelf in yards rather than feet. The quantity {(3.0, ft/yd), length conversion factor} has the property that when used in a multiplication or a division, it does not change the nature of the referent but only the numerical description of its measure. Unit measure conversion factors are thus special sorts of intensive quantities that can be used freely in order to achieve consistency of measures.[9] One can now return to the question of how to compare or find the sum and/or difference of the two volumes {(2, ft3), volume} and {(144, in3), volume} Using suitable unit measure conversion factors allows us to say that {(2, ft3), volume} and {(3456, in3), volume} are equivalent volumes as are {(144, in3), volume} and {(0.0833, ft3), volume}. While it is straightforward enough to make comparisons of magnitude of the two volumes expressed in common units, the question of what sense is there in forming their sum and/or difference remains exactly as it was before - the arithmetic operations of addition and subtraction may not be reasonable models of the referent situation. e. do we need scalars?There is another intensive quantity that merits special attention. This kind of intensive quantity is like the unit measure conversion factor in that it does not change the nature of the referent of the quantity on which it operates. However, it does change the magnitude of its measure. It is normally called a scalar and is assumed to have no referent (Vergnaud 1983). When one says that the weight of a second grader is {52.5, lb, body weight} and that the weight of an eighth grader is twice as much, is not the weight of the eighth grader obtained from that of the second grader by multiplying by the pure nominal number 2? It is possible to adopt the position that the scalar quantity is better represented by {2., lb/lb, ratio [8th grader/2nd grader] body weight} It may seem awkward to “complicate” the problem of doubling the weight by forcing the 2 to carry the unit lb/lb. Another example will make the need for doing so clear. Suppose one wants to enlarge a photograph and one asks the photographer, “Please make me a copy of this picture that is twice as big.” The request seems to be ambiguous. Is it intended that the enlarged picture have linear dimensions that are twice as big as the original, or is it intended that the area of the enlarged picture be twice as big as the original? This issue is immediately resolved if the word “twice” is understood to mean either {(2, cm/cm), ratio of lengths} or {2, cm2/cm2), ratio of areas} It should be pointed out that this sort of intensive quantity, the scale conversion factor, has the property that its numerical magnitude is independent of the particular (dimensionless) intensive units in which it is measured. Finally, let us observe that quantities of this form will allow us later to extend our generalization of the arithmetic of adjectival quantity to algebra and calculus in such a way as to make those subjects broadly accessible tools for modeling the world around us. f. more about multiplication and divisionThe (I I' I") and (E E' E") Semantic Triads Although the (I E E') triad accounts for the vast majority of the multiplication and division operations we ask students to undertake, there are other kinds of triads of quantities related by multiplication and division operations. These other structures are I x I' = I" and E x E' = E". as well as their associated division structures. An example of a multiplication of the first sort, I x I' = I", is {(33.3, mi/gal), fuel efficiency of car on trip} x {(1.5, gal/hr), car's rate of burning fuel on trip} = {(49.95, mi/hr), average speed on trip}[10]. The second sort of multiplication, E x E' = E", is an example of the formation of a Cartesian product. Here are some specific examples; Discrete x Discrete {3, blouses} x {5, skirts} = {15, outfits} Discrete x Continuous {400, passengers} x {(1000, miles), distance} = {400000, passenger-miles), volume of traffic} Continuous x Continuous {3.20, cm, width of rectangle} x {6.40, cm, length of rectangle} = {20.48, sq cm, area of rectangle} Both the (I I' I") and the (E E' E") semantic triads share with the (I E E') triad the property that the multiplication operation maps a quantity in one space onto a quantity in another space. On the other hand, they differ from the (I E E') triad and from one another in significant ways. The I" intensive quantity, {(49.95, mi/hr), average speed on trip} in the case above, is itself a relationship, i.e. one that describes any of, or indeed all of, an infinite ensemble of trips, each of which involves a time and a distance that are related through the intensive quantity. On the other hand, the E" extensive quantities, {15, outfits} {(400000, passenger-miles), volume of traffic} {20.48, cm2, area of rectangle} are not relationships between two extensive quantities. Each of these quantities is an extensive quantity in its own right. In contrast, however, to the extensive quantity E' which is produced in the (I E E') triad, the referent E" in the (E E' E") triad is an entirely new kind of referent. This new extensive quantity represents an expansion of the semantic space of the problem and it remains to be defined along with its measure. In our examples, we note the fact that a blouse-skirt is precisely what we mean by an outfit, that passenger-miles is a possible measure of volume of traffic and that the product of two lengths is an area measured in sq cm in this case. Notes [1] It should be pointed out that an intensive quantity need not have the word per appear explicitly in its unit measure. Often it is implicit as in the case of the knot or nautical mile/hour for example. Another interesting case of an intensive measure in which the word per does not appear explicitly in the unit measure is temperature. A degree on the temperature scale is a measure of the average kinetic energy per particle in a material. The non-obvious intensivity may contribute to the substantial difficulty that many adults as well as students have in distinguishing between heat and temperature. [2] It should not be assumed from these examples that an intensive quantity is necessarily a scalar quantity. There can be vector, second rank tensor, etc. intensive quantities. [3]To be sure this quantity can be represented as a point on a single meter/second number line. Doing so, however, hides its relationship to both distance and time as quantities. [4]Note that the product of a quantity with the referent candies/bag and a quantity with the referent bags gives rise to a quantity whose referent is neither candies/bag nor bags. [5]We note that the result of executing the division of one discrete quantity by another need not be a new discrete quantity. In fact, it will almost always be the case that such a division will result in a quotient that is 'continuous' (strictly speaking rational rather than real) and that is not restricted to integer values. [6]Later, after having been

introduced to the decimal system students are taught that the result of this

division is {5.5, candies/bag}. If the candies are discrete, then no single bag

can have this number of candies and the quantities can only be statistically

descriptive of the situation. To make the point more strongly, think of

children/family rather than candies/bag. [7]I became acutely aware of the price of not doing this when a student one day described to me the three Ohm's Laws he learned in physics. He quoted them as voltage = current x resistance, current = voltage / resistance and resistance = voltage / current. [8]Even more disturbing to people is the reciprocal of this quantity {(.4, families/child), ...}! [9]One should not conclude that any quantity whose unit is the ratio of common attributes such as length/length or time/time is a unit conversion factor. For example one can characterize a clock that runs slowly as losing time at the rate of {(1.5, seconds/hour), clock's rate of losing time} or {(1/2400, seconds/second), clock's rate of losing time}. [10]Strictly speaking, the product should be {(50.0, mi/hr), average speed} because the measured quantities in the first factor of the product is known to be larger than {(33.25, mi/gal), fuel efficiency}and smaller than {(33.35, mi/gal), fuel efficiency} and in the second factor, larger than {(1.45, gal/hr), rate of burning fuel} and smaller than {(1.55, gal/hr), rate of burning fuel}. |