This paper presents excerpts from an early version of a paper that was written by Michal Yerushalmy and me and that was published in For The Learning of Mathematics, Vol. 15,

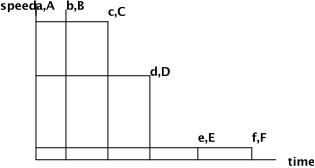

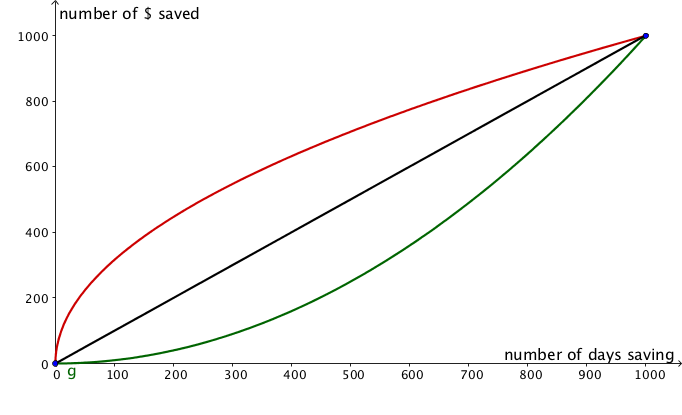

No. 2, 1995 On The Need For A Bridging Language for Mathematical Modeling There are many people, we among them, who will argue that mathematics has the importance it has in the school curriculum because it provides people with a set of analytic tools for dealing with the quantitative aspects of their world. Doing so requires people to mathematize the situations that they wish to analyze. Normally, we think of the problem of mathematizing a situation as one of identifying elements of the situation that we deem important for the purpose at hand, and then identifying pertinent relationships among those elements (again, for the purpose at hand). The first step in this process is to move from the perceptions and measurements of the actual situation to a verbal description of the elements and relationships that hold among them. The task then becomes one of formalizing this verbal representation of the situation. This procedure is called modeling. Modeling is incorporated into the learning sequence of mathematics for two reasons: for exemplification and application [Nesher (199x), deLange (198x)]. It is this second reason that is normally offered to justify its introduction in arithmetic, algebra and calculus word problems. Fashioning models offers students an opportunity to analyze applied situations and mathematize them using the symbolic language that they have been taught. It will be recognized this happens only after students have mastered the language of symbolic representation that is needed to express their models. Thus it is usually the case that application of the mathematics to situations in their world is something that students do only very late, if at all, in their mathematical careers. Mathematical language is necessary for exemplification as well as for application. We use examples to motivate, interest and engage our students. However, the ordinary language in which situations are described is insufficient for mathematical analysis. Normally in the course of mathematics instruction, one assumes that in dealing with real-world situations that it is sufficient to use common parlance and not concern oneself overly with precise descriptions. Precision of language is usually reserved for the "abstract" and "formal" and appears at a later stage of instruction. In practice the act of mathematization is taught only in part. In school mathematics people are presented with verbal descriptions of situations (rather than the situations themselves), that are carefully crafted to contain all the needed (and sometimes extraneous) information necessary "to solve the problem". They are taught to make a list of "givens" and "to be founds". This action corresponds to the identification of elements described above. They are then told to assign symbols to these elements and to write relationships among these symbols drawing on the language of mathematics for the verbs (operations) and adjectives (quantifiers) that are needed to make propositions linking the nouns (elements) they have chosen. The lack of precise language is a less serious problem with elements that when modeled turn out to be nouns, than it is with relationships which normally require other mathematical "parts of speech" for their articulation in a mathematical model. One notes that while some explicit attention is paid to the problem of sensitizing people to the need for identifying elements of a situation and representing them symbolically, little or no effort is addressed to the problem of helping them to express the relationships among these elements. Perhaps this is the case because there is no convenient representation available that lies between that of the senses that perceive the situation and the natural language that humans use to communicate with one another on the one hand, and the sparse and often impenetrably semantically dense symbols of mathematics on the other. We seek therefore to address the problem of providing the same sort of sparse linguistic representation for relationships that is parallel to what lists of "givens" and "to be founds" provide for elements of situations to be modeled. The approach we propose capitalizes on the ability of people to represent many types of relationships graphically (Chazan, 1994, Kaput 199x, Schwartz 198x). The linguistic representation we propose here is intermediate between the complex natural language in which problems are often formulated and the dense and precise analytic and symbolic representation of the mathematics. This intermediate linguistic representation is based on the function, which we have claimed elsewhere (Yerushalmy and Schwartz 1991) is, for pedagogic reasons, the appropriate fundamental object of secondary school mathematics. The linguistic representation we propose has two distinct sorts of lexical items, icons and words. As we will see, there are synonymous relationships among the iconic and verbal lexical elements of this intermediate linguistic representation. A word of caution, however. Even though statements articulated with one sort of lexical item can be restated using the other sort, it is the case that the two distinct sets allow for different degrees of definitiveness. For example, describing a function n a region as being "increasing" and "curved" is far less of a limitation on the function than is the display of a particular increasing and curved function. Embedding the manipulations of the two linguistic sets in a software environment makes it possible for students of mathematics to express themselves with either sort of lexical item, and permitting the software to display equivalent synonymous statements in the other sort. Appropriately designed software, in which students may choose to talk about functions in the generality offered by words or the particularity offered by images can make explicit the distinction between the two sets of lexical items. In order to make our proposal clear, we offer a simple example upon which we will comment in some detail. Consider the following problem: A car was traveling along at 65 miles per hour for 1 minute until the driver spotted a police car. Over the course of the next minute, the driver slowed down to the speed limit of 40 miles per hour and immediately spotted a suspected traffic jam up ahead. Slowly at first, and then faster and faster over course of the next minute, the driver slowed down to 25 miles per hour. At that point it became clear that the car would be unable to more than creep along at a very slow and steady 5 miles per hour, the driver quickly adjusted her speed to the speed of the crawling traffic over the course of the next minute. Calculate both an upper and lower bound to the distance the car traveled during the time it was slowing down from 65 miles per hour to 5 miles per hour. We do not propose to solve this problem here. We wish simply to step back and ask what is important to be understood about this situation. We wish to focus our attention on the flow of events without the distraction of the specificity of the numbers. Here is a rewritten description of the situation that allows us to focus on the flow of events. a car was traveling along at high speed until the driver spotted a police car. The driver slowed down to the speed limit and traveled at the speed limit until spotting a suspected traffic jam up ahead. Slowly at first, and then faster and faster, the driver slowed down. When it became clear that the car would be unable to more than creep along at a very slow steady speed, the driver quickly adjusted her speed to the speed of the crawling traffic. The story may separated into a sequence of events. Each event is characterized by a time of its occurrence, indicated by a lower case letter, and the action that either took place at that time or was taking place at that time, indicated by an upper case letter. a: our story starts A: driver traveling too fast b: driver spots police car B: driver begins to slow down c: driving at speed limit C: spots potential traffic jam d: driver decides that she won't have to stop entirely D: starts to slow down more slowly e: driver stops slowing down E: car travels at steady crawling speed of traffic f: end of the story F: car crawling along This parsing of the story into a sequence of events suggests that a useful graphical representation of the situation might be had by plotting these events qualitatively in a Cartesian speed-time plane. Our understanding of the situation is clearly more complete than these points, by themselves, would indicate. We know qualitatively how the speed of the car changed during the times between the events that we singled out in our parsing of the story. Here is a possible representation of that variation. The graphical form of the functional variations that we have used here are drawn from a complete set of graphical icons that allow us to represent any reasonably well behaved function of one variable. It is this set of graphical icons (and their corresponding verbal labels) that constitutes the sparse linguistic representation for relationships that we mentioned earlier. These icons taken as a group can be used to form graphs of both simple and complicated functions. One can imagine each icon being freely stretched or squeezed horizontally. In addition, each icon can be anchored at either its left or right end point and stretched or squeezed vertically to the extent that its defining properties continue to obtain. For example, an increasing function with decreasing change (derivative) may be deformed by horizontal and vertical stretching so long as the function remains increasing and the change remains decreasing. Within very wide limits any "reasonable" function of a single variable can be piecewise approximated by these "deformable" icons. Now that we have a language available for describing piecewise functional relationships, we can ask the persons solving the problem to use this language to link the successive events that they see as the major elements of the situation. Here, as before, the italicized language is supplied by the users of the software as a way of attaching verbal labels to the end points of the intervals of the deformable icons. Here is the story as reconstructed from the events and the graphical icons used to link them. First event: a,A time: our story starts what happened: driver traveling too fast between first event and next event ( a < time < b) speed of car is constant rate of change of speed of car is zero Next event: b,B time: driver spots police car what happened: driver begins to slow down between this event and next event ( b < time < c) speed of car is decreasing rate of change of speed of car is increasing Next event: c,C time: driving at speed limit what happened: spots potential traffic jam between this event and next event ( c < time < d) speed of car is decreasing rate of change of speed of car is decreasing Next event: d,D time: driver decides that she won't have to stop entirely what happened: starts to slow down more slowly between this event and next event ( d < time < e) speed of car is decreasing rate of change of speed of car is increasing Next event: e,E time: driver stops slowing down what happened: car starts traveling at steady crawling speed of traffic between this event and next event ( e < time < f) speed of car is constant rate of change of speed of car is zero Final event: f,F time: end of the story what happened: car crawling along We believe that it is appropriate and indeed pedagogically important that people learning both algebra and calculus learn to do this sort of qualitative description of situations that they are asked to mathematize. We view this problem as representative of all modeling problems that involve timevarying situations. Thus the language introduced above is not specific to speed-distance problems. Rather it can serve as the first formal stage of communicating analyzing and reasoning about such situations. Here are a few examples in which the use of this kind of linguistic parsing plays an important role in the understanding of students while they are in the process of mathematizing a situation, without the distraction of symbol manipulation. I. A problem requiring analysis UP, DOWN & NEITHER - A CALCULUS FANTASY The were once three sisters whose family name was Up. Their names were Florence Shirley Up, Shirley Up, and Florence Francis Up. Needless to say, there was much confusion about their names. Their friends gave them nicknames to help tell them apart. Here is a table showing the given names and the nicknames of the Up sisters. given name nickname Florence Shirley Up Fast Start Up Shirley Up Steady Up Florence Francis Up Fast Finish Up How did it come about that these three sisters were given such peculiar nicknames? When they were quite young children, the three Up sisters decided that they would each save $1000 in 1000 days. But they each went about it quite differently. Shirley Up would put away one dollar every single day and needless to say at the end of 1000 days she had saved $1000. Florence Francis was not very interested in putting money in the bank. At first she put away very little. But on each succeeding day she put away more than the day before. At the end of the 1000 days, she too had saved $1000. Florence Shirley on the other hand was really quite eager to start saving. She started enthusiastically, but she gradually lost interest. At first she put away a lot. But on each succeeding day she put away less than the day before. At the end of the 1000 days, she too had saved $1000. Here is a graph of how much money each of the sisters had in the bank on each of the 1000 days. • Who was saving the most money every day at the beginning of the 1000 days? • Who was saving the most money every day at the end of the 1000 days? • Can you tell from the graph approximately when Fast Finish (Florence Francis) first started to put away as much money every day as Steady (Shirley)? • Can you tell from the graph approximately when Fast Start (Florence Shirley) first started to put less money in the bank every day than Steady (Shirley)? • Can you tell from the graph if there was ever a day when Fast Start (Florence Shirley) and Fast Finish (Florence Francis) put the same amount of money in the bank? • Assume the bank pays interest. Who do you think will have earned the most interest? II. A problem requiring inference WATER IN A RESERVOIR The Quabbin Reservoir in the Western part of Massachusetts provides most of Boston's water. The graph below represents the flow in and out of the reservoir throughout 1993. • Sketch a possible graph for the quantity of water in the reservoir, as a function of time. • When, in the course of 1993, was the quantity of water in the reservoir largest? Smallest? • When was the quantity of water decreasing most rapidly? • By July 1994 the quantity of water in the reservoir was about the same as in January 1993. Draw plausible graph for the flow into and the flow out of the reservoir for the first half of 1994. Explain your graph. (Hughes-Hallett 1994, p.325) These two examples provide an arena for the analysis of a process and its change. The problem that we posed at the beginning of this paper requires, to some degree, an analysis of the accumulation of a process. This is a much harder problem to model, since it forces people to draw conclusions about the accumulation of a process by analyzing its change rather than drawing conclusions about the change of a process by analyzing its accumulation Like all inverse processes, it tends to be more difficult. (Symbolically, we note that integration is both algorithmically and pragmatically more difficult for students.) Toward this end we have developed a software environment[1] that is designed to facilitate the doing of this sort of qualitative analysis. _ _ _ _ _ Further Thoughts Although this approach to the problem of mathematical description has much to recommend it from a pedagogical point of view, it is limited in at least two respects. First, the punctuating events of the setting being described and the deformable graphical icons used to link them may be semantically too primitive. Second, the deformable graphical icons do not uniquely identify analytic forms. Let us explore each of these problems in greater detail. The Primitive Nature of the Icons The icons used in the example given above are quite widely useful across a range of situations. However, it is quite possible to encounter situations in which these icons, while in principle applicable, are not as informative or provocative of deeper analysis as a different set might be. For example one might wish to describe the behavior in time of an undamped oscillating system. The behavior is periodic and the iconic approach proposed here would require the parsing of the behavior of the system into "chunks" that run from minimum to maximum and from maximum to minimum of the variable being depicted. It will be noted that there are two types of "chunk" that alternate with one another. These "chunks" are then assembled alternately to display the behavior in time of the system. It is at least possible to argue that this is an awkward way of requiring students to think of periodic behavior. One can throw the problem into somewhat bolder relief by considering the motion of an oscillating system with light damping. Under these circumstances, the motion ceases to be strictly periodic, but is still characterized by a series of alternating maxima and minima equally spaced in time. The alternate "chunks" in this instance are no longer identical. Indeed in this case one would be better served by thinking of the form of the function as resulting from the multiplicative product of an oscillating primitive and a monotonically decreasing (e.g. exponential) primitive. This example suggests to us that it would be valuable to be able to modify the depicted graphical representation of functions in two ways. First, we would like to be able to build composite objects, such as periodic functions, and turn them into "primitive" graphical entities in their own right. Second, we would like to be able to modify the graphical representation of functions, not only by direct graphical deformation as we have described, but also by being able to carry out binary (and unary) operations between and on functions. The Implied Analytic Forms and their Non-uniqueness A second difficulty with the approach proposed here is that the analytic forms suggested by the icons are not unique. For some purposes this presents no difficulty. If, however, one wishes to explore the nature of the function with greater delicacy it is necessary to introduce ways to measure the rapidity of a function's change and even the rapidity of change of the function's change. For example, in some regions the graphs of x2 and 2x look very similar. The analysis of the change shows that in the quadratic the change is proportional to the independed variable (meaning: a straight line) while in the exponential the change is a curve and seems to change proportionally to the function itself. We consider such analyses important one since they direct a student's attention toward an understanding of the properties of functions rather than to mechanical manipulations of the sort that all too often characterize a student's first encounter with these ideas in mathematics. Pedagogical Implications: The approach and the software[1] described above is an important part of a newly developed curriculum. Findings from research on the implementation of this curriculum are described elsewhere (Yerushalmy , in prep.). However, here, we would like to identify a few of the major effects of approaching mathematics in the qualitative way we have described above. Imagine a tetrahedron. The vertices of the tetrahedron are elements of different representations - they are symbolic language, numerical language, graphical language and NATURAL language. Ultimately we want our students to be able to use all of these representations with some agility. Traditionally we formulate instruction so that it proceeds from symbols to numbers and from there (sometimes) to graphs. This path forces students to master algebraic rules and manipulations, as well as symbolic manipulations of families of functions before being able to use the mathematics for the purpose of modeling his or her world. We believe that this is an important reason underlying the fact that so little time is devoted to modeling and important mathematical inquiry in the secondary school curriculum. This path also implies a serial learning and teaching style rather than one that makes use of multiple parallel linked representations; students spend most of their learning time manipulating symbols without even able to connect what they are doing to numbers (Lee and Wheeler 198x) or to graphs (Dugdale ????). Graphs, if studied at all, are always the last representation to be studied and are seen, all too often by teachers and students alike, as a visual consequence of manipulating numbers and symbols. In this new formulation it is possible to begin with any of the representations that correspond to a vertex of the tetrahedron and to proceed to any other representation. For example, one can start by using situations described in natural language and mathematize them using qualitative graphs whose properties are put forward in natural language (Chazan 1994). It is then the need for more precise language that leads to the necessity of introducing symbols. The manipulations of symbols are mirrored as transformations in each of the other representations as well. Some of the transformations are found to preserve the qualitative character of the graphs and the natural language but appropriately change the structure of the expressions. This path is based on the conviction that modeling provides both an important reason for teaching algebra and an important strategy for doing so. Another path though the vertices of our tetrahedron would start with purely numerical problems and build the need for all representations of functions of a single variable on the formulation of numerical patterns. Such patterns can be represented graphically and the analysis of these graphs can then lead students to the need for symbolic representation. Currently it is well documented that students see little need for symbolic language and often confuse the concept of variable with the mechanics of manipulating unknowns. (Lee 199x, Schoenfeld 199x...). In that case modeling enters the curriculum at the application phase (in contrast to the previous path, in which modeling served as exemplification phase for the establishment of the major concepts.) Of course, there is no correct path through the vertices of the tetrahedron. Looking at the tetrahedron one can devise and explore other ways to help students link the mathematical concepts and their representations that underlie algebra and develop some facility with a variety of mathematical actions. However one chooses to go about this, we find it hard to imagine how it might be done without a delicately crafted set of curricular environments in which there are mathematical objects and actions that may be carried out on and with them, and in which the qualitative language of mathematics can play a significant role. [1] The software described in the original paper but not presented here is long outdated and no longer available Judah L. Schwartz  mathMINDhabits by Judah L. Schwartz is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |