This paper originally appeared in the Harvard Educational Review, Feb. 1989, 59(1), p. 51. The version that appears here is slightly updated and refers to applets that appear on this website that existed in the late 80's only in the imagination of the author. For those readers interested in pursuing how the issues raised in this essay were instantiated in schools with students, please refer to "The Geometric Supposer: What is it a Case Of?", J.L. Schwartz, M. Yerushalmy, B. Wilson (eds.), 1993, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ. A discussion of earlier work on Intellectual Mirrors can be found in J.L. Schwartz, "Software to Think With: the case of algebra" in D. L.

Ferguson, Ed., Advanced Educational Technologies for Mathematics and Science, Berlin, Springer-Verlag, 1993.

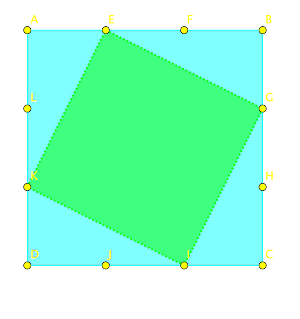

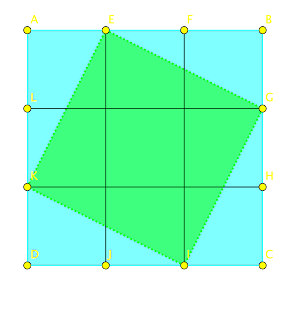

Intellectual Mirrors: A Step in the Direction of Making Schools Knowledge-Making Places Mathematical Creativity in the SchoolsFor the most part, the mathematics we teach in the primary and secondary schools is the mathematics already made by other people. Were we to teach language in that fashion, we would ask the students to learn a play by O'Neill, an essay by Emerson, a short story by Hemingway, but we would never ask them to write prose of their own. I believe that students have a right to be challenged to create in every field they study in school. Further, I believe that schools have the obligation to challenge students to create in every field they ask students to learn. In some subject areas such as English composition and art, students, their parents, and society have come to expect schools to offer the challenge of creating. In mathematics this is rarely the case. Given the difficulty teachers have in teaching mathematics and students have in learning it, one might think that this is a hopelessly quixotic goal, one that stands little chance of being realized. Before rejecting this goal, however, it is worth exploring for a moment or two what the essence of creativity in mathematics is and whether or not its realization is so utterly unreasonable. I believe that the essence of mathematical creativity lies in the making and exploring of mathematical conjectures. Let me explain what I mean. A mathematical conjecture is a proposition about a hitherto unsuspected relationship thought to hold among two or more mathematical objects. What is a mathematical object? A mathematical object is a formally defined construct such as a number, a shape, a vector, a matrix, a function, and so forth. In general, for each mathematical object there will be one or more defined mathematical operations that can be carried out on the object and that can transform it in some way. Thus, for example, the operation of reciprocation transforms the number 2 into the number 0.5 and the operation of shearing transforms a rectangle into a parallelogram and a square into a rhombus. Suppose we grant that the essence of mathematical creativity is the making and exploring of mathematical conjectures. Why have such activities not been a serious part of mathematics teaching and learning in the schools? I believe they have not because this sort of conjecturing activity is difficult to carry out without suitable tools and because such tools have begun to come into widespread use only very recently. If people lack tools that make the trouble associated with the making and exploring of conjectures manageable, they simply are not likely to be interested in doing so. One such tool is a software environment called the GEOMETRIC SUPPOSER that provides a setting and an occasion for conjecture and creativity for both student and teacher in the mathematics classroom. Following a description of the SUPPOSER, I will try to abstract the properties of this and other pieces of software that belong to a genre of educational software that I call "intellectual mirrors." Finally, I will consider the lessons that the experience with "intellectual mirrors" may have for the design of software in other disciplines that could promote invention and creativity in the same or similar ways. An Overview of the GEOMETRIC SUPPOSER The GEOMETRIC SUPPOSER is the collective name of a series of programs developed at the Education Development Center (1). Perhaps the best way to introduce the SUPPOSER is to explain something of the cognitive conundrum that math teachers encounter when they set out to teach geometry. It seems fairly evident that the human cognitive apparatus needs the external aid of drawings and diagrams in order to think about spatial and visual matters. Nevertheless, as soon as one moves to answer that need by either making or providing diagrams to be used in the learning of geometry, for example, one runs the risk of defeating one's own purposes. Here is the heart of the matter. Consider, for example, the class of shapes that we call regular polygons. We can construct a regular polygon with three sides, with seventeen sides, or with any particular number of sides, but we cannot construct a regular polygon with N sides. Similarly, we can construct any particular triangle, but we cannot construct a triangle that is any triangle. If we construct a diagram of a triangle, then, aside from the size of the triangle there is only one such triangle. It should be noted that this is in sharp contrast to the situation in algebra, where the notation system allows us, for example, to write F(x) = mx + b to denote any function whose graph is a straight line. The geometry we wish to learn, teach, and make does not deal with the properties of particular shapes but rather with the properties of classes of shapes. How are we to resolve this seeming conflict between the cognitive need for diagrams and images on the one hand, and the necessarily particular and specific nature of those diagrams on the other? Suppose that, starting with a particular triangle, we make some construction and discover that in this case some interesting property obtains. Clearly, we wish to know whether or not this interesting property is true for other triangles as well. One can view the construction made on the original triangle ABC as a procedure that takes the three points in the plane ABC as its argument. In less mathematical language, we can imagine the same construction being done again starting with a different original triangle labeled ABC. If the environment is such that the procedure is executed in terms of a manageably small number of elemental procedures, then it is possible to have the computer capture the steps of the procedure. The captured procedure can then be repeated on a different original triangle or, in more mathematical language, on any other triplet of points in the plane. Although this repetition of the procedure is clearly incapable of proving anything, it can lead to heightened or lessened conviction that the property observed to be true in the particular case is indeed generally true. Both the psychological and logistical costs of making the conjecture and exploring it are thus dramatically reduced. An Example of a Geometric Escapade with the SUPPOSER To give the reader a better sense of what happens in a classroom in which teacher and students are engaged in making much of the geometry they deal with, I present here a miniature case study of challenge and invention adapted from a classroom interchange that took place over several days (2). The students involved were enrolled in what their school system called an "average ability" track, but had a teacher committed to challenging his students to create and invent (3). Our story opens with the teacher's raising of the following question: Consider a square ABCD. Subdivide segment AB into three equal segments AE, EF, FB. Similarly, subdivide BC into BG, GH, and HC, segment CD into CI, IJ, and JD, and segment DA into DK, KL, and LA. (See Figure 1.) FIGURE 1 Now draw segments EG, GI, IK, and KA. What interesting things can be said about the quadrilateral EGIK? The first thing to notice is the way the problem was posed by the teacher. Normally, in a geometry class, a problem is posed in the form: Given . . . Prove . . . Here, in contrast, students must discern which properties of the quadrilateral EGIK they believe to be both interesting and true. As a result, students gain experience in that most-neglected part of the curriculum, the art of problem posing. I cannot adequately stress the importance of this issue. I believe that intellectual independence and initiative result far more often from a diet of problem posing and solving than from the far more restricted, but more common, diet of problem solving. Further, since many things are true about EGIK, some more interesting than others, considerations of taste and judgment begin to enter into a domain that most people regard as cut, dried, and completely known. Most of the students suspect that the quadrilateral EGIK is a square. They bolster their confidence in that suspicion by measuring angles KEG, EGI, GIK, and IKE. Each turns out to be 90 degrees. But how does one know that this is not a measurement error, since not even computers can measure with complete accuracy? Would the same be true for a different square ABCD? Using the Repeat option of the SUPPOSER, students examine the construction and measurements for another square ABCD. Here too the angles turn out to be 90 degrees. By now the conviction that EGIK is a square is fairly strong. But the students know that strong conviction and proof are two different things. After all, there is an infinite number of possible squares, and even if one assumes there is no error of measurement, one cannot measure all possible squares. The students feel that a formal proof is needed, and they produce one, using pencil and paper, without too much difficulty. The students then pursue another line of inquiry. Someone suggests that since ABCD and EGIK are both squares, it might be interesting to know the ratio of their areas. A measurement is made, yielding a ratio of 1.8. Using the Repeat option, they examine a few more squares, and the ratio 1.8 is found to be true in each instance. Most of the students are satisfied to go on to something else, but two of them persist in exploring the question of the ratio of the areas. Why 1.8? One of them says that 1.8 is an ugly number! Much head scratching follows, and then, with a broad grin, one of them exclaims: S1: It's not 1.8! It's 9/5. S2: But 9/5 is 1.8. S1: Yeah, but look . . . and he quickly draws segments EJ, FI, GL, and HK. (See Figure 2.) Square ABCD is thus subdivided into 9 smaller squares, the central one of which lies entirely within EGIK. The remaining space in EGIK is easily seen to be equal to the areas of triangles EBG, GCI, KDI, and AEK, each of which has an area equal to 1/9 of ABCD. Thus the area of EGIK is equal to 5 of the smaller squares that cover ABCD. Hence the ratio 9/5. FIGURE 2 [Click here for and interactive version of this exploration] This is a remarkable insight, but the story doesn't end here. In fact, the story hasn't ended yet because these students, with the enthusiastic encouragement of their teacher, then made a series of conjectures proposing totally new geometric results that are still not entirely proved or disproved. Here is a sample of some of the directions they pursued. Suppose one hadn't subdivided the sides of the original square into 3 equal parts, but rather into 4? Into 5? . . . into 100? Into A? How about into 2? . . . or into 1? Would the resulting quadrilateral still be a square? What would the ratio of the areas be? The students solved this problem shortly after they posed it. Suppose that one had divided each side of a parallelogram or a kite or a trapezoid or even some random quadrilateral into three equal segments and constructed the quadrilateral EGIK. What kind of a quadrilateral would one get? What would the ratio of the areas ABCD to EGIK be in such a case? This problem seems to have a startling result — that is, that the ratio of the areas of the shapes ABCD and EGIK is still 1.8. I do not know whether anyone has yet produced a complete proof or disproof of this result. Suppose one started not with a quadrilateral but with a triangle, a pentagon, a hexagon, or . . . an N-gon? [Click here to explore this question] Some things are simple and straightforward, some are not. Can one generalize the problem to more than two dimensions? How? This one is a stumper! The moral of this story is that the students ended up exploring a hitherto unexplored piece of mathematics. They posed and solved new problems. They came to understand the importance of formal proof as a way of establishing mathematical truth or falsity when dealing with infinite classes of entities, all quadrilaterals, for example. They developed an appreciation of the fact that mathematics is a live and lively discipline that continues to grow and evolve. As a direct consequence of the realization that mathematics is not a spectator sport, roles in classrooms must and do shift. It is no longer possible for teachers to serve as ex cathedra authorities, nor is the authority of the text beyond question. Teachers and students must and do learn to listen carefully to and assess the quality of one another's arguments. Further, teachers who work with their students and their subject matter in a way that allows students to explore their own understanding often come to think of themselves as people who continue to learn the subject they are teaching. In my view this is a necessary, albeit insufficient, condition for being a good teacher. This story about the SUPPOSER, and others like it, have been taking place in growing numbers of geometry classrooms around the country for about five years. It is a source of considerable pleasure to me, as one of the designers of the software, that there seems to be no consensus about the audience of students for whom the software is best suited. Many teachers who have used the software report that they believe it is particularly well suited to students who have previously shown themselves to be mathematically adept and interested. By contrast, many teachers in schools with hitherto unsuccessful mathematics programs report that using the SUPPOSER has changed student attitudes toward, and performance in, mathematics (4). Before we leave the discussion of the SUPPOSER, it is worth reviewing those features of the software that could serve as the basis for defining a genre of software that might be of broader interest than geometry and mathematics. First, the SUPPOSER has no explicit instructional agenda; it asks no questions of the user and makes no inferences about the user's intentions. Second, the SUPPOSER'S primitive operations — that is, the menu options that the user can choose — are germane to plane geometry. They are, however, more elaborated than the simplest straightedge and compass constructions of Euclidean geometry; they include such constructs as parallel, perpendicular, angle bisector, and so on. Primitives such as these are simple enough to be understood in terms of the simplest straightedge and compass constructions, on the one hand, and complex enough that their concatenation can lead to nontrivial new mathematics, on the other. Third, the facility of the SUPPOSER that allows users to capture their procedures and to explore, through direct observation as well as measurement, the effect of these procedures on other members of the same class of shapes directly confronts users with the question, "What is this construction a case of?" The SUPPOSER is thus a tool for exploring particularity with an eye toward the problem of generality. The SUPPOSER doesn't necessarily induce users to greater degrees of generalization, but it helps to provide, along with an encouraging teacher and challenging written materials, the setting and the occasion. Software, Inductive Thinking, and "Intellectual Mirrors" The central proposition of this article is that the SUPPOSERS are special cases of a more general genre of software environments in which users, be they students or teachers, can explore an intellectual domain. In these cases the domain in question is Euclidean plane geometry. Because the software environment reduces the difficulties associated with the exploration of the domain and indeed provides rich tools for such exploration, those who have access to such an environment can, with the appropriate stimulation, use that access to explore the domain. I say appropriate stimulation because I believe that, for most of us, problem posing and problem solving are in large measure social activities. We need the stimulation of our peers, our students, and our teachers. Mathematics is peculiarly appropriate to the creation of such exploratory environments. This is because mathematics, like other formally defined domains, allows for the rigorous articulation of the entailments of any set of given conditions. In any exploratory environment in which this is possible, conjectures appropriate to the domain can be made, using the set of tools made available by the environment. Such environments can display quickly the result of testing a conjecture. Using such environments as "intellectual mirrors," it is possible for users to probe their own understanding of a domain, as well as to devise new relationships among the objects of the domain. In such environments it becomes inviting and engaging to think inductively and to explore one's inductive notions. Similarly, the environment and its tools invite users to generalize their thinking and to examine the range of validity of those generalizations. The mental acts of thinking inductively and generalizing are at the heart of what we would like our mathematics students to learn to do. I assert that appropriately designed software environments can help us reach that goal. What properties should such exploratory environments have? I doubt that I can give a complete characterization. However, I shall attempt to offer a broad outline of the properties I believe to be essential to such environments. What "Intellectual Mirror" Software Should Know In my view, the software should know what it needs to know about the domain — that is, it should understand formal manipulations of the objects it is designed to manipulate. It should not pretend to know about the user — that is, it should not make inferences about the intentions of the user. If the user asks the software to execute a formally allowable move, it should do so, mirroring the user's action with its entailments without trying to infer whether or not that move brings the user closer to a goal the nature of which the software may not know. Such decisions must always be made by users, possibly with the aid of a set of utilities, such as measurement tools in the case of the SUPPOSERS, that allows users to examine more closely the detailed properties of the consequences of their actions. Primitive Operations in "Intellectual Mirrors" In my view, to the maximum degree possible and feasible, the primitive operations in "intellectual mirror" software should be germane to the domain that is its subject. Doing this requires the designers of the software to take the subject matter seriously and to base their choices of primitive operations on a deep analysis of the subject. Every temptation to incorporate extraneous features should be resisted. No apologies need be made for the fact that a given environment might not permit any imaginable exploration. In short, an "intellectual mirror" is, and ought to be, something less than a full-fledged programming language. Systems that do not possess this property often make it difficult for the user to understand the relationship between actions taken and consequences observed. The Fallacy of Logical Parsimony Mathematicians and mathematics educators see great beauty in the logical parsimony of their discipline. Academics in other formal disciplines are probably equally enchanted with the aesthetics and elegance of their disciplines. In my view, it is important to suppress the urge to make the primitive operations of an "intellectual mirror" environment be the formal primitives of the discipline. Rather, it is desirable to make them intermediate composite constructs that are built from the formal primitives of the subject matter. They should be sufficiently elementary that it is possible to concatenate them richly and still have the newly constructed objects remain within the intellectual grasp of the user. The design of such primitive operations for "intellectual mirrors" is in large measure a problem of pedagogic artistry. Capturing Particularity, Inferring Generality Much of mathematics, and indeed any formally defined subject, can be described as a sequence of structures, each embedded in a structure of increasing generality. An "intellectual mirror" environment should have the property that the exploration of any particular structure can also be carried out at a greater level of generality that includes the first level as a special case. Looking back, in what sense can the GEOMETRIC SUPPOSER be said to be an "intellectual mirror" environment? First, it has no built-in pedagogic agenda; it asks no questions and therefore is in no position to make inferences about answers. Second, its primitive operations are not the most parsimonious constructs that can be concatenated to formulate the discipline it deals with, but rather are a more richly elaborated set of primitives. These primitives are reasonably close to the elementary operations of the formal system of plane geometry. Indeed, they are sufficiently close to the most elementary constructs of geometry so as to be readily understandable in terms of them. At the same time, they are rich enough in structure that their concatenation can lead to interesting and nontrivial insights into the subject matter. Finally, the SUPPOSER, by virtue of its ability to capture a user's construction in a particular case and repeat it on an unlimited number of other cases that belong to the same class, provides a special and supportive environment for allowing students to understand how the particularity of their efforts fits into a larger mathematical generality. "Intellectual Mirrors" in and out of Education Some final comments about "intellectual mirrors" are in order. The first is that one ought to distinguish between computer tools for learning how to do some task and computer tools for doing that task. For example, in the last two decades computers have come to be both the palette and the canvas for engineering design. A good computer-aided design (CAD) system can be expected to have, among its many capabilities, many of the features of the SUPPOSERS. Nonetheless, one cannot reasonably regard a CAD system as a suitable environment for the teaching, learning, and making of Euclidean plane geometry. The utility of a CAD system depends on the depth and breadth of its features, which are generally much more extensive than those geometric issues that the SUPPOSERS are trying to address. Under such circumstances there is a real risk that learners using the system may well lose sight of the geometric fundamentals in wrestling with the problem of learning the system. For the most part, in devising "intellectual mirror" environments for mathematics, we are concerned with the task of designing tools for introducing people to a domain, rather than tools that allow knowledgeable users to apply the tools of the domain to other ends. The second comment is linked to the first and is an extension of the remark I made above in discussing the knowledge that "intellectual mirror" software should have. The point here is that our ultimate goal is the education of people. We seek to educate them both to know some mathematics and to make some mathematics. The responsibility for doing this must ultimately lie with them. If one agrees with this premise, then the current fashion of turning to "artificially intelligent" software that tries to infer users' intentions or software that itself "knows" or "makes" mathematics in order to improve mathematics education is misguided. A learner using such a system has the problem of not only understanding the domain that he or she is struggling to master, but also of trying to understand what motivates the computer's heuristic responses. On the other hand, if the computer responds algorithmically and predictably to inputs from the user, then the image in the "intellectual mirror" is a faithful reflection. What Does the Future Hold? This has been a quite personal and idiosyncratic view of an important role for the microcomputer in mathematics education. I believe that the arguments presented here can be extended to include any subject based on formal definition and formal reasoning. A growing number of students and teachers in this country and abroad (5) have had experience learning and teaching with the GEOMETRIC SUPPOSERS in real schools and in conditions constrained by the demands of real school settings. On the other hand, the conjecture about the extension of these ideas to other formal subjects is mine alone and is still a matter of speculation. The validity of the conjecture remains to be established. Lest I be misunderstood, let me be clear that I support with enthusiasm attempts to create "intellectual mirror" software in the widest possible variety of other domains. Suppose that, encouraged by the success of these efforts in mathematics, we succeed in building environments in other domains that allow people to explore their own understandings. Suppose, further, that we are willing to augment our notions of subject matter so that the making of new content is an endless process to be engaged in by students and teachers. Finally, suppose we are willing to rethink what we think we understand about the roles of students and teachers. If we do all this, we may well be standing at the threshold of a new era in education. This material has been reprinted with permission of the Harvard Educational Review for personal use only. Any other use, print or electronic, will require written permission from the Review. For more information, please visit www.harvardeducationalreview.org or call 1-617-495-3432. Copyright © by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved. (1) The Education Development Center (EDC) was established in the late 1950's as a nonprofit research and development center with the goal of helping improve education in this country and abroad. It has carried out over two-hundred projects ranging widely over subject areas and audiences. (2) This example is drawn from Michal Yerushalmy, "Induction and Generalization: An Experiment in Teaching and Learning High School Geometry," Diss., Harvard University Graduate School of Education, 1986. (3) For the purpose of understanding the example the reader should know the following about the GEOMETRIC SUPPOSER: Quadrilaterals, from which the example is drawn. The Main Menu has the following items: DRAW MEASURE LABEL SCALE ERASE REPEAT NEW SHAPE The submenu of DRAW allows the user to draw line segments, circles, parallel and perpendicular lines, and to bisect angles. The submenu of LABEL allows the user to label intersections of lines, subdivide line segments, reflect points and lines in lines, and place points at random inside, outside, or on shapes. The submenu of ERASE allows the user to erase labels, lines, and data. The submenuof MEASURE allows the user to measure angles, lengths, and areas. The submenu of SCALE allows the user to rescale the construction on the screen. The submenu of REPEAT allows the user to repeat the construction and measurements on the screen on another quadrilateral. The submenu of NEW SHAPE allows the user to put a new quadrilateral on the screen. The quadrilateral may be a randomly generated parallelogram (or any more restricted subclass of parallelograms), trapezoid, kite, or inscribable or circumscribable quadrilateral. In addition, users have the option of constructing their own quadrilaterals. (4) Michal Yerushalmy, Daniel Chazan, and Myles Gordon, Guided Inquiry and Technology: A Year Long Study of Children and Teachers Using the Geometric Supposer. Technical Report 88-6 (Cambridge: Educational Technology Center, Harvard University Graduate School of Education, 1987). (5) I have been told about the use of the SUPPOSERS, either in experimental or regular classrooms, in the Federal Republic of Germany, Israel, and the Soviet Union. In the United States, based on figures supplied by the publisher, I would estimate that at the time of this writing (late 1988) there are several thousand classes using the SUPPOSERS. |