This paper was presented at a

seminar in the Faculty of Science & Technology at The New University of

Lisbon, Portugal, in June 2002

Introduction In the fall semester of the 2001-02 academic year I gave a course entitled “Models, Simulations & Exploratory Environments” to the students in the Technology in Education program at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. It was the first time I had offered the course. Although I was convinced that the subject was an important one, and that I had a reasonable idea of the range of issues that I thought should be covered, I did not have what I considered to be a satisfactory framework for thinking about the subject. The course description read; In many ways the greatest promise of computers is the amplification of human intellectual power by allowing us to explore complexity and to manipulate easily the abstract constructs we formulate. To do this, we often build models and simulations in order to instantiate our theories of real phenomena. These models and simulations are of necessity simplifications and idealizations that attempt to capture the essential features of those aspects of the physical and social world they describe. The widespread availability of inexpensive computation has led to an extraordinary growth of the use of models and simulations for analysis in the natural and social sciences. This course will focus on the exploration of a variety of widely available existing models and simulations. We will attend, in particular, to the ways in which the theories of the model-builders are expressed in the models they build and to the inherent limitations on the fidelity of models. The course that I offered was a kind of “smorgasbord” that followed the course description touching on topics that I was certain were important. I spent a good deal of the time, both during the course and after it was over, reflecting on possible larger frameworks that would allow me to relate the various and seemingly disparate elements of my “smorgasbord” to one another. This paper constitutes my first attempt at setting down such a framework.

Some useful caricatures of extreme views about models and their role in education In thinking about a complex problem it often helps to define dimensions whose polar extremes are clear caricatures. One of the virtues of doing so is that one is forced to confront the nuance of complexity by thinking carefully about where on a spectrum between the extremes any given case might fit. Here are three pairs of polar extremes that have helped me think about models and their role in education.

Let us explore each of these in turn.

I. models vs. simulations

The following questions come immediately to mind. What do we mean by models? What do mean by simulations? Are there meaningful distinctions between these two terms? If so, how do they resemble and differ from one another? Finally, since both models and simulations, whatever we might mean by those terms, certainly allow us to pose “what if” questions, how do models and simulations resemble and differ from exploratory environments that also support the same sort of inquiry? Both models and simulations are artificial environments that refer to some external “reality”. Both contain a collection of entities. The attributes of (some of) these entities and (some of) the relationships among these entities are incorporated into the model or simulation. Certainly to this extent models and simulations are similar. In my view an important difference arises when one considers the purpose of fashioning the artificial environment, i.e. the model or simulation. Recognizing the caricature-like nature of the distinction I submit that the purpose of making a model and exploring it is to expose the underlying mechanisms that govern the relationships among the entities. In contrast, the purpose of making a simulation and running it is to provide users with a surrogate experience of the external “reality” that the simulation represents. Thus models seek to “explain” complex referent systems while simulations seek to “describe” referent situations, often by offering rich multi-sensory stimuli that place users in as rich a simulacrum as possible. Given this difference in purpose it is not surprising the makers of models seek to limit the complexity of their models so as to make the underlying causal and/or structural mechanisms more salient. In contrast, designers of simulations tend to incorporate as much of the richness and complexity of the referent as possible so as to make the experience of using the simulation as rich a perceptual experience as possible. In the educational context this difference in purpose points to quite different roles for models and simulations. Consider a natural or social science curriculum. In the elementary grades the emphasis is on having the students exposed to a rich repertoire of phenomena. For these students well-designed simulations can complement direct observation of nature, compensating for spatial and temporal remoteness or mismatch of scale to the human perceptual apparatus[1]. Secondary students, on the other hand, need to learn about correlations and underlying causes. These are best explored in models that make these correlations and causes salient without the overlay of complexity that can so readily disguise them. This difference in purpose between models and simulations leads to another interesting difference between them. Models tend to make their underlying generative rules accessible and visible to the user. In contrast, simulations most often hide their generative rules from the user. Indeed in many instances the generative rules of simulations do not at all reflect what is known about the generative rules of the referent situation.[2] These distinctions are summarized in the following table.

In contrast to models and simulations exploratory environments refer to model-building environments. They may have no particular referent domain as in the case of programming languages – we will describe these environments as domain general. Examples include: Modellus[3], Worldmaker[4], Link-It[5], Agentsheets[6], StarLogo[7], Stella[8], etc. On the other hand, they may have restricted domains such as “supposers” of all sorts – we will describe these environments as domain specific. Examples include: Geometric Supposer[9], Geometer’s Sketchpad[10], Cabri Geometre[11], Genscope[12], Interactive Physics[13], Newtonian Sandbox[14], Tarski’s World[15], etc. Domain-general exploratory environments allow users to generate models to explore in a wide range of domains limited mainly by the imagination of the user and the input-output affordances of the computing environment. Thus, in Stella, for example, people have written economic models, ecological models, psychological models, sociological models, models of chemical systems, models of physical systems, etc. Domain-specific exploratory environments allow users to fashion microcosms that they may then explore. For example, the Geometric Supposer allows users to make Euclidean geometric constructions and explore the effects of modifying measures and constraints. Its use in schools has led to many dozens of new theorems discovered by students.[16]

II. function(process) vs. structure(constraint) models

The second set of polar extremes that I find useful in thinking about models and their use in education is the contrast between models based on structure and models based on function. II.1 Function-based models Much of the excitement in the world of education about the use of using computer-based models and simulations derives from an enthusiasm for having students follow the evolution in time of the system being modeled or simulated. I refer to such models and simulations as function- or process-based. Independent of the degree of complexity and/or verisimilitude embedded in the model or simulation, function-based models and simulations have the property that the passage of time for the user engaged in the model or simulation is a scaled version of the passage of time in the referent system.[17] Before proceeding to a discussion of the several type of function-based model a word is in order about the underlying mathematics and its algorithmic articulation. Function-based models are typically expressions of sets of differential equations with time as the independent variable or difference equations with sequence number as the independent variable. Such models have the property that they relate the state of the system at one instant of time to the state of the system at the “next” instant of time[18]. In order to be able to compute the evolution of such a model in time one must specify an initial state of the system so as to be able to begin the computation.

II.1.1 Spatially distributed function-based models In some ways spatially distributed function-based models are easier to understand conceptually despite the fact that the underlying mathematics is more complex than that of other kinds of function-based models. In a spatially distributed function-based model one specifies how the values of the variables of interest at a given point in space and a given instant of time depend on the values of the variables at that point and at “neighboring” points in space in the immediate past[19]. Spatially distributed models can be formulated in different numbers of spatial dimensions. In one dimension, for example, one might write a model of the conduction of heat along a metal bar one end of which is maintained at a fixed temperature. The output of the model is the temperature of the bar as a function of position along the bar and the way in which the temperature at every position along the bar evolves in time. Another interesting application of one dimensional spatially distributed function-based models is in the study of traffic flow along a highway. A spreadsheet is often the most convenient tool for the writing of such 1D function-based models. Spatially distributed function-based models can also be written in two dimensions. They are particularly useful for the study of predator-prey phenomena, epidemiological phenomena, housing patterns, etc. Consider for example an array of cells each of which has either grass or bare soil. In some of the cells there are rabbits. A very simple set of rules governs the evolution of this system. If a rabbit finds itself on a cell with grass it eats grass. If it finds itself on a cell with a neighboring cell unoccupied by a rabbit, then there is some probability that it will move to the next cell. If there is a neighboring cell that is unoccupied by a rabbit there is some probability that the rabbit will reproduce and cause the neighboring cell to be occupied by a rabbit. There is some probability that a rabbit on a cell containing soil will die. Cells containing soil that are adjacent to cells containing grass grow grass. This very simple set of rules suffices to produce a model that allows one to explore the relationship between the availability of food and density of animals that consume that food. This is an example of a class of modeling environments called “cellular automata” that lend themselves particularly well to the writing of such models.[20] Finally, one can write spatially distributed function-based models in three spatial dimensions. Models of the atmosphere used for weather prediction are typically of this form. The atmosphere is divided into cells. The values of the temperature, wind velocity and air pressure in a given cell at a given instant of time depend on the values of these quantities in that cell and neighboring cells in the immediate past. Models such as these tend to be enormously demanding computationally and their utility on the educational scene is somewhat dubious.

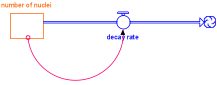

II.1.2 Lumped variable function-based models A second kind of function-based model ignores the spatial distribution of the variables of interest.[21] The underlying mathematics is that of coupled first order differential equations converted into the appropriately corresponding difference equations in order to allow for numerical computation. A particularly interesting environment for the writing of such models is called STELLA. It permits users to state relationships among variables and their rates of change graphically. Once the model is thus partially defined in terms of the qualitative relationships among the variables, the user is prompted to supply those quantitative values that are needed by the model in order to compute the time evolution of the system. Here, for example, is a STELLA model of radioactive decay. The essential variable is the number_of_undecayed_nuclei.

number_of_undecayed_nuclei(at time {t}) =

number_of_undecayed_nuclei(at time {t-Δt}) + (- decay_rate) * Δt

INITIAL number_of_undecayed_nuclei = 10000

OUTFLOW: decay_rate = .1*number_of_undecayed_nuclei

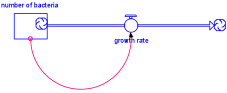

The qualitative relationship in the model was defined by establishing a variable called number_of_nuclei (in the diagram), and its rate of change whose magnitude is controlled by a quantity called decay_rate. The size of the decay_rate is related to the number_nuclei. Then once the initial number of nuclei is specified the model may be evolved in time. It should be pointed out that all phenomena that decay exponentially can be reasonably modeled in this fashion. Moreover, all phenomena that grow exponentially can also be modeled in this fashion simply by changing the sign of the decay_rate, thus turning it into a growth rate. Here for example is a model of the exponential growth of a colony of bacteria:

number_of_bacteria(at time {t}) =

number_of_bacteria(at time {t-Δt}) + (growth_rate) * Δt

INITIAL number_of_bacteria = 10000

OUTFLOW: growth_rate = .1*number_of_bacteria

The similarity in model structure is apparent. Mathematically this is a particularly simple example and one that can be solved analytically by any first-year calculus student. However, the modeling environment is far more permissive in terms of the functional forms it allows people to explore. The constraint of analytic solubility that limited exploration of complex systems to simple soluble cases is no longer a serious obstacle to our building and exploring models.

II. 2 Structure-based models Not all useful models involve systems that evolve in time.

II.2.1 Spatial structure-based models Consider the following two objects - an airplane model built on a 1/100 scale (e.g. 1cm represents 1 meter) and a model of a benzene molecule built on a scale of 100,000,000/1 (e.g. 1 cm represents 10-8 cm). Clearly each of these can be useful in educating people. In what sense are these objects models? They are models in the sense that each represents the form of a referent object on a grossly different spatial scale. Moreover, their various parts represent spatial interrelationships among the various parts of the referent objects. For example, the model airplane may have a wingspan that is 1.2 times as long as the fuselage of the model airplane, reflecting the corresponding relative sizes of parts in the airplane being modeled. Similarly, the model of the benzene molecule constructed, say, of colored balls connected by short sticks, is essentially planar (flat) and hexagonal. The real benzene molecule, made up of carbon and hydrogen atoms is also planar and hexagonal. It is interesting to note that there is a sense in which each of these models is made for essentially the same reason, i.e. to bring into comfortable human perceptual range an object that is much too large or much too small to otherwise study carefully. That having been said, one is led to ask - just what is it about the referent object (airplane or molecule) that can be studied with the model? It seems to me that models of this sort are primarily useful for studying the spatial properties, both topological and geometric, of their referent objects. If one is interested in the flow of air around the wings and fuselage of an airplane, one can study the problem using a model only by exercising extreme caution. While one can readily make a 1/100 scale model plane there is no way to scale the size of the air molecules flowing past the airfoil in the wind tunnel. Similarly, the stresses on the fuselage of a model are not related in any simple way to the stresses on the fuselage of a real airplane. Using models of the very small also presents problems. Carbon and hydrogen atoms are not blue and white spheres and there is no sense in which they can be said to have sharp boundaries. In fact, there is no sense in which they can be said to have color at all! The primary use of such models based on structure is the study of spatial interrelationships in the referent objects. As the user contemplates a models airplane or model benzene molecule, the passage of time bears no relationship to the system being studied.

II.2.2 Non-spatial structure-based models There is a class of models that allow users to explore explicit relationships among a set of related variables. Consider, for example, the phenomenon of the height of a thrown projectile, a subject studied in all introductory physics classes. If we denote the height by y, the initial height by y0 , the initial vertical velocity by v0 , the acceleration due to gravity by g, and the elapsed time since the projectile was thrown by t, one can write a relationship that relates all of these quantities to one another. That relationship is

y – y0 – v0t + ½ gt2 = 0.

Any one of the quantities y, y0, v0, g in this relationship can be written as an explicit function of the time t. In like manner, any of the quantities y, y0, v0, g may be treated as the independent variable instead of the time t. If one holds y0, v0, and g constant and systematically varies t while observing the variation of y, one can observe the behavior in scaled time of a real system. Suppose, however, that one holds y, y0, and g constant and varies t while watching the changing values of v0. Even though we are systematically varying time in this case, it is not scaled time in some real referent situation. It is rather a depiction of how one parameter of a complex situation depends on another. To drive this point home consider the relationship among the following three quantities: the pressure of the gas in a container P, the volume of the container V, and the temperature of the gas T. This relationship, studied extensively in all chemistry and many physics classes, is known as the Perfect Gas Law. It can be written as PV = aTwhere the constant a is related to the amount of gas in the container. Clearly one can hold V constant and systematically vary T watching the behavior of P as one does so. Similarly, one can hold T constant and systematically vary V watching the behavior of P as one does so. In neither case does elapsed time for the user of the model have anything to do with the temporal behavior of the system. In fact, the model describes a system in equilibrium, and as such, contains no explicit reference to time. It should be pointed out that a very large fraction of the spreadsheet models used by business analysts around the world fall into this category of non-spatial structure models.

III. learning by using models vs. learning by making models

The third set of polar extremes is learning by using models vs. learning by making models. Wilensky[22] argues strongly, in the tradition of Papert[23] and his followers in favor of students being provided with powerful modeling building environments with an eye toward their building their own models of interesting referent situations. This stance is set in opposition to having students use previously built models as arenas for exploration. His arguments, which are characteristic of this perspective on the use of computers in education, are summarized in the following table[24].

The contrast drawn between the two perspectives would lead one to believe that they are in profound opposition to one another. In practice, the dichotomy turns out to be a false one. Students most often encounter modeling in education through the use and exploration of models written by teachers or other authors of curriculum. At first their use of models tends to be exploration by the modifying of the parameters of the models. Next they are often asked to modify the models themselves, thus providing them with a range of related models to work with. Finally, students make be asked to devise models of phenomena ab initio[25] It seems to me that the good sense of teachers is well expressed in this sequence. Students who have little notion of the purpose of a model and the ways in which they enable people to explore their own understanding will probably not benefit greatly from the writing of their own models, if indeed they can learn to do so at all. In my view, pedagogic artistry lies in helping students move through this sequence in ways that are appropriate to the depth and breadth of their understanding of the subject as well as their mastery of the mechanics of the modeling environments available to them. For example, it is perfectly reasonable to ask secondary students to write their own models of motion using simple force laws in simple constraint geometries. Such models as they write might then be explored and provide insights and deepened understanding. On the other hand, if such students are asked to write their own models of incompletely understood complex systems, they are likely to become bogged down in the complexity and learn precious little about either the system or the process of modeling. I am led to the following conclusion about this third set of polar extremes. It is neither reasonable nor efficient to expect students to invent for themselves the content of contemporary disciplines by modeling. They do, however, need to learn the content and the limitations of the best models now in use in their fields of interest. However, students do need to have enough experience with modeling to understand the point of modeling, its strengths and weaknesses, and to appreciate that the scientific progress of mankind lies in the continual reexamination of old models and the devising of new ones.

[1] Simulations of a rain forest allow urban students to overcome one kind of spatial remoteness. Simulations of an urban transport system allow rural children to overcome another kind. Simulations of the night sky that show the trajectories of the planets over several years during the course of several minutes help to overcome a mismatch of temporal scale. Etc., etc. [2] Consider, for example, an animation of a running horse or a melting ice cube. Most animations are made by “tweening” i.e., interpolating frames between drawn (or photographed) initial frames. The same algorithm that is used for animating the running dog could be used to animate the melting ice cube. The algorithm that the software uses for interpolating frames has nothing to do with the musculature of the dog or the properties of ice and water. [3] http://phoenix.sce.fct.unl.pt/modellus/ [4] http://worldmaker.cite.hku.hk/worldmaker/pages/ [5] See for example Learning with Artificial Words, Mellar, Bliss, Boohan, Ogborn, Tompsett (eds.) London, The Falmer Press, 1994 [6] http://www.agentsheets.com/ [7] http://el.www.media.mit.edu/projects/macstarlogo/index.html [8] http://www.hps-inc.com/Education/new_Stella.htm [9] http://www.cet.ac.il/math-international/software1.htm [10] http://www.keypress.com/index.html [11] http://www-cabri.imag.fr/index-e.html [12] http://genscope.concord.org/ [13] http://www.interactivephysics.com/ [14] http://webassign.net/pasnew/newtonian_sandbox/newtsand.html [15] http://www-csli.stanford.edu/hp/Logic-software.html [16] See, for example, Schwartz, Judah L., “Intellectual Mirrors: A Step in the Direction of Making Schools Knowledge-Making Places”, in Harvard Educational Review, Vol. 59, No. 1, February 1989 and J.L.Schwartz, B. Wilson & M. Yerushalmy, (eds.). The Geometric Supposer: What is it A Case Of?, Hillsdale, New Jersey, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 1993 [17] One allows here for the possibility of 1:1 scaling of time, i.e., that model time proceeds at the same rate as referent system time. [18] Because time, as a continuous variable, is replaced by a discrete variable the ordinarily meaningless locution “the next instant of time” has meaning. [19] Typically this means that the model is an expression of a coupled set of partial differential equations that are first order in time. [20] I include under this general heading environments that make use of “sprites” such as StarLogo. These environments may be thought of as generalizations of cellular automata in which cells do not have fixed location and are not obliged to interact with near neighbors only. [21] Indeed the variables of interest may not have spatial extent at all. In modeling immigration policy, it is often important to define variable like immigration rate and availability of jobs without concern for how these quantities vary from place to place. Of course, a more detailed model may try to take this kind of variation into account. [22] See Wilensky, U., GasLab: An extensible modeling toolkit for connecting micro- and macro-properties of gases, in Modeling and Simulationin science and Mathematics Education, W. Feurzeig & N.Roberts, eds. New York, Springer-Verlag, 1999, pp.151-178 [23] See for example Papert, S., Mindstorms: Children, computers and powerful ideas, New York, Basic Books, 1980 [24] See note 22. [25] It is interesting to note that in his paper describing GasLab (note 22) Wilensky describes his students as proceeding through this same sequence from learning using models to learning making models.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||